Comfort Conversations: Mike Savicki On Being a Disabled Veteran

In early November 1990, less than three months before his 23rd birthday, Mike unofficially, unwillingly, and unwittingly became a veteran of our nation’s military. While some might consider earning the title an honor, he didn’t. And while some might be eager to begin the transition back to civilian life, he wasn’t.

Let me first share some background information. Before I was born, my father served as an officer on a replenishment ship in the Navy. He wore the uniform, deployed overseas and even had a few military stories that he shared with me when I was a kid. He never went to war, but told me that when he took the oath, going to battle was something he was prepared to do.

I’d wear parts of his old dress whites and even button on his khaki uniform, too. He taught me how to polish brass, shine shoes and do a proper salute. I think that’s where the seeds of service were planted in me.

What It Means to Mike to Have Worn Our Nation’s Uniform

So, as a kid, I started to paint a picture of what a veteran should look like. He (or she) was older, perhaps a parent, like my dad, or a grandparent. He had uniforms hanging in the closet, stories to share, lots of buddies at the local coffee shop, and was a member of an organization like the VFW or AMVETS. A veteran was someone who marched in parades, visited schools, and flew an American flag in the yard.

A veteran wasn’t a fit, athletic, intelligent, strong, confident, 22-year-old recent college graduate like I was on that early November day. So at first I shunned the label because I still wanted to serve. I wanted to deploy and see the world. I wanted to earn ribbons and pin medals on my dress whites. And because aviation was what I had planned to do, I wanted to fly.

I wanted a jet with my name painted below the cockpit canopy just like in the movie, Top Gun. I wanted a pilot’s call sign before being called a veteran.

An emergency room doctor was the first person to tell me I was a veteran. He shared the news as I lay on my back with my neck immobilized by something called a halo cast, screws in my skull, IV tubes crisscrossing my body, machines monitoring my systems.

“Well, your Navy career wasn’t a long one,” I think I recall him saying. “And I’m not sure you’ll get to sail the seas, see the world, and I know you’ll never fly jets, son.”

“You broke your neck and you are pretty lucky you didn’t drown in the process,” he continued. “You have some function in your arms and shoulders but no movement below your chest, and I’m pretty sure you won’t be getting much more back than what you have right now. When you hit the bottom, you fractured your cervical vertebrae and a bone chip severed your spinal cord. You’ll never walk again and you will need a wheelchair to help you in life.”

His diagnosis was my unofficial welcome to the veteran world. The official welcome letter came several months later in the form of U.S. Navy discharge papers saying that because of my injury, I was unfit to continue to serve.

Mike Struggled with Being Discharged Due to Disability

I wasn’t quick to accept the news. At the time of my injury, I was more worried about having left the sunroof of my new sports car open in the Pensacola Beach parking lot after I was helicoptered away and whether I had gotten blood on my favorite set of board shorts, than I was about being paralyzed.

“Your car should be the least of your worries, son,” the doctor added. “And as for your bathing suit, we cut that off a few hours ago when you first arrived.”

I was covered only by a hospital sheet and had no feeling below my level of injury. I’d never drive that car again. What the doctor was telling me had some truth to it.

Through the years, I have grown into the label and, looking back on the definition of veteran that I formulated as a kid, I know a lot of it is true.

Yes, my old uniforms hang in my closet, I have an American flag in the yard, and I’m a member of three veteran service organizations – PVA, DAV and MOAA. I have attended more parades than I can count and have spoken at schools, too.

While my military stories don’t involve wars and battles, I can at least recall the one time I got to pilot a Navy jet, soaring high above the California desert east of NAS Miramar as part of my early, injury-ended flight training, pulling more G’s than a NASCAR driver pushing 200 mph on a superspeedway.

I’m older now, too, a husband and a father, and I have grey hair like most veterans my dad’s age did when I was young.

Mike Embraces His Differences…and His Strengths

What is different is my disability. My wheelchair doesn’t limit who I am; it complements the person I have become. With it I have rolled across a graduation stage, traveled the world, and competed in many different sports.

I have a closet full of medals earned in competition. And I get the rock star parking spaces, too. At age 48, I have developed a sense of American pride I never thought possible.

When strangers thank me for my service, I tell them it was an honor.

A few years ago, my town dedicated a veteran’s monument into which are etched the names of every resident who has served in the military dating back to the founding. When I first saw my name in granite, I realized that the memory of my service would live on beyond my years. Whenever I drive by it, I pause…even if just for a moment.

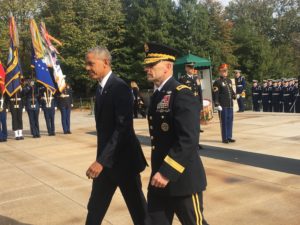

On November 11, 2016, I had the honor of attending our nation’s annual Veteran’s Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery as a guest of the Paralyzed Veterans of America. I look forward to gathering alongside our nation’s heroes, honoring those who have served, and saluting those who have sacrificed. Veterans alike.

On November 11, 2016, I had the honor of attending our nation’s annual Veteran’s Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery as a guest of the Paralyzed Veterans of America. I look forward to gathering alongside our nation’s heroes, honoring those who have served, and saluting those who have sacrificed. Veterans alike.

And as I age with a disability, I see younger veterans coming back from service, many with disabilities similar and different, and I jump at the chance to work with them. I share tips about adaptive sports, I counsel them on the “ins and outs”  of wheelchair use, I answer their questions no matter what they are, and I ask them about their service, too. In their young faces I see the physical, mental and emotional scars of battle and I ask myself what might have happened to me had I deployed overseas and served in a forward position like them. Then I think to myself, yes, we are all veterans, but we are all individuals, too, with our own unique experiences, adversities and struggles.

of wheelchair use, I answer their questions no matter what they are, and I ask them about their service, too. In their young faces I see the physical, mental and emotional scars of battle and I ask myself what might have happened to me had I deployed overseas and served in a forward position like them. Then I think to myself, yes, we are all veterans, but we are all individuals, too, with our own unique experiences, adversities and struggles.

To those who gave their lives in service, I will be eternally grateful.

This essay was originally published on Wheel:Life, a website to which Mike regularly contributes. You can find it at http://wheel-life.org/comfort-conversations-on-being-a-disabled-veteran-with-mike-savicki/.